Ultima Online’s influence

This is the first question I’m answering from the ones I got for UO’s 20th anniversary.

This is the first question I’m answering from the ones I got for UO’s 20th anniversary.

I never played UO, so not knowledgeable. Maybe a routine question, but how do you think #UltimaOnline pushed the genre forward?

This is a big question.

I think we should start with a look at what the world was like in 1995, when the project was formally launched. Most people connected to the Internet via modem, and many of them were on 14.4k or 28.8k speeds. The 56K modem didn’t come out until 1998.

For comparison, my cable Internet at home gets 70.7Mbps for downloads. That’s 70,700k per second, versus 14k or 28k. The bandwidth difference is almost 2,500 times as much, if we look at the 28.8k modem. And that’s not counting speeds – ping times everywhere are quite a bit faster than they used to be. Old routers used to add 20ms just from you going through them, and getting 250ms ping time to anywhere was considered normal and if sustained, pretty good.

Mosaic launched in January of 1993, and Netscape Navigator in 1995. Until Mosaic, the web didn’t have pictures. There was no Google, but there were Yahoo! and Webcrawler. Amazon launched in 1994 but only sold books and wasn’t a big deal yet. There were only around 100,000 websites on earth. Your dial-up internet service provider fees would be in the range of $20-30 a month.

Internet discussion happened mostly on Usenet, though there were some fledgling Internet forum BBSes, and of course things like The WELL and discussions on the many closed online services like Prodigy, America OnLine, and CompuServe. This latter one charged by the hour — $5 to $16 per hour – and was flailing enough that AOL bought it. (Prodigy had pioneered flat rate pricing a few years earlier).

Prodigy streamed each screen down as an image, even the text ones.

Gaming, of course, was alive and well, including online gaming. The top games in 1997 included Final Fantasy VII, Goldeneye 64, Castlevania, Star Fox 64, Parappa the Rapper, The Curse of Monkey Island, Age of Empires, Mario Kart 64, Fallout, X-Wing vs Tie Fighter, Theme Hospital, and Total Annihilation. Max game resolution, if you had a powerful rig, was generally 800×600.

During the development of UO, we carefully watched the development and release of Diablo and heaved a sigh of relief when we realized it was a graphical version of Rogue or NetHack, rather than a persistent world (today people toss around “roguelike” as a common term. It didn’t use to be). I remember a bunch of us gathering around one computer to play the demo version. Its graphics were much better than what we were already committed to, but its multiplayer was very limited. “That is forbidden in the demo” is still an occasional catchphrase in our house – our research sessions always ended there at the last doorway in the single-level demo.

WorldsAway was derived off of Habitat

Quake had come out in 1996, and many of the art team played it on the company LAN in the afternoons. Most online gameplay was LAN play, in fact; services like DWANGO (launched in 1994) allowed LAN games to be played over the Internet using a dedicated dial-up service that served as a matchmaker. Around 1995 to 1996 TEN and MPath (aka MPlayer, and eventually GameSpy) showed up, and started bundling games with LAN play into a subscription that let you play them online via the Internet. These services varied in price from $30 a month to $30 a year, on top of ISP fees, but by and large didn’t offer much if any persistent world gaming (TEN had Dark Sun Online which came out in ’96).

There were MMOs, for sure. You can read over the timeline to see just how many preceded Ultima Online – quite a lot, particularly if you count all the text-based worlds, as I do. Simutronics had its text-based MUDs running, such as DragonRealms and Gemstone. Mythic was their competitor. WorldsAway, a version of Habitat, was on CompuServe, as were Islands of Kesmai and Air Warrior. The aforementioned Dark Sun Online and also Lineage were played in the UO offices during the development process as well, though they were both in pretty rough state.

Meridian 59, like EverQuest after it, started out with a small game window with inventory and chat boxes around it

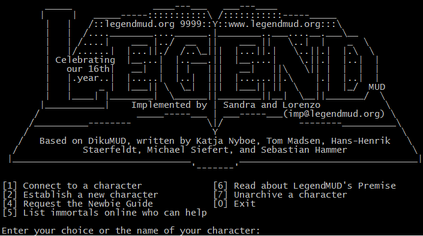

And of course, Meridian 59 beat UO to market as well. Sometime in 1995 or so, Mike Sellers logged into LegendMUD, and I toured him around. If I was online, I often greeted newbies personally, and if they were people involved in creating MUDs, I would offer to tour them around the game, showing off the many things that it did that were different from the run of the mill. After the tour, Mike talked to me about a possible job on Meridian 59, and I turned him down because Origin had already made an offer. I recommended Damion Schubert for it instead.

Lineage, when I first tried it, consisted of one house, that you stepped out of onto a killing field and basically died immediately. DSO was much larger, but had some sort of turn-based combat. If you got hit, you were put into the turn sequence for everyone in the fight; this resulted in a blob of dozens of players waiting a half hour to swing once or try to escape the fight. (I honestly don’t know whether this was a bug at the time or what – I never played it again). Sierra had launched The Realm in 1996; it had a side view, and each fight was actually an “instance” – when you engaged in combat with another entity, outsiders saw a cloud with fists and whatnot poking out, and you were sent to another screen to do battle.

Ultima Online COULD have been DragonSpires, but Origin decided to build their own

As Richard Garriott, Dr. Cat, and others tell it, the idea for an online, multiplayer version of the Ultima series had been around for quite some time. There was an abortive deal with Sierra to create a “Multima.” Dr. Cat, a long-time Origin veteran who had left the company, was interested enough in online gaming that he created a game called DragonSpires which was way ahead of its time, and the predecessor to Furcadia. Richard and Starr Long went to the executive greenlight board at Electronic Arts multiple times trying to get money to fund a prototype, and after being turned down each time, finally got a check for $150,000 or $250,000 (I have heard varying figures) directly from Larry Probst, the CEO.

When they went looking for people make the game, they ended up having to look outside the company, and the place to look turned out to be MUDs. I’ve told the story elsewhere of how they found Rick Delashmit, and from there they found my wife and I as designers, where we had cut our teeth in online world design on LegendMUD.

LegendMUD soft-launched in ’93 and officially Feb. 14th, ’94. At least five Legend players were involved with UO & the early MMO industry.

The state of the art in MUDs was quite different from what was going on in online services. Most of the games on the online services were basically hack and slash with quests. Most of the most popular MUDs were also hack n slash, the Diku style of game, which due to its hard-coded nature didn’t have much in the way of interactivity with objects and NPCs. LegendMUD, and the mud we had played before it, called Worlds of Carnage, were different from other Dikus. Thanks to an embedded scripting system, they had much more interactive worlds more akin to what was happening in the MOO and LPMud circles.

In MOOs, MUSHes, and LP’s, the use of scripting and domain-specific languages had opened up enormous potential for virtual worlds. Some of these kinds of worlds handed over coding capabilities to end users. Some didn’t, but because they were dramatically easier to mod than a Diku, had all sorts of experimental things going on. Bear in mind we’re talking text-based games running on computers far less powerful than your typical smartwatch, but MUDs were exploring design ideas such as

- Player driven voting systems and player governments.

- Procedurally created zones.

- “Roomless” worlds where the descriptions of locales were procedurally generated based on what landmarks were in nearby coordinates.

- Agent-based AI systems where creatures had more autonomy and a bit of an ecology.

- Spellword languages for dynamically creating magic.

- Roleplay-mandatory worlds with permanent death.

LegendMUD itself was notable for having things like vehicles you could drive or fly, ships you could sail, furniture you could sit in, a rich chat system with moods and adverbs, a spell-word based magic system, an herbalism system that used the pharmacological properties of real world herbs, an out of character lounge anyone could teleport to, and more.

A lot of the discussion on features like this came from the fabled MUD-Dev mailing list, run by the redoubtable J. C. Lawrence. And it was on MUD-Dev where the designers and programmers of all the above games ended up gathering and swapping ideas and debating the future of online worlds. Out of this ferment came Ultima Online.

When we posted up the first FAQ for UO on our skunkworks domain owo.com (“Origin worlds online”) in 1995 or early 1996, a black website with little suns and llamas on it, and a giant long list of promises written in text, it was not only the first website ever created within Electronic Arts, but it also was a bit… ambitious. (Alas, the text seems lost to history).

Given all the above context, here are some things that Ultima Online attempted, and mostly pulled off.

I’ll start with the least remarkable, which was pure scale. A tile-based seamless world that was 4km on a side, with multiple biomes. Further, one that supported multiple floors, in 2d isometric, and 3d terrain texture mapping. Although the art wasn’t as detailed as Diablo, this was something they (and most any 2d game competitor) simply couldn’t do. Being able to walk upstairs or into a basement in a building in game was startling at the time. Having actual 3d sloping terrain of any sort, likewise; most 2d games still faked elevation changes with optical illusions.

A tile-accurate map of UO, reduced by about 50% or so. Not including dungeons.

This map was enormous, for the time. So was the art asset load. There were sixty-one unique models for creatures, and each, though modeled in 3d, was output into sprite frames – 15 frames per animation, in eight directions. Forty-eight weapons. And hundreds of small items of many sorts, many of them interactive. In text games, you see, it had been easy to just invent more items, and we wanted that freedom in UO. Consider that the average number of items you could pick up or interact with in other graphical MMOs at the time was, for most locations, zero.

And all this was in service of supporting 2500+ people at once in a given world, literally ten times what other worlds typically supported. (Linux at the time even came out of the box with a limit of 250 or so file descriptors). More people in one world, interacting. If anything, the map was too small, which led J. C. Lawrence to call the game “a hothouse.”

Scale was one thing, but a key difference in UO was that this stuff was actually used in more than one way. To my knowledge no previous 2d RPG had ever shown all your equipment on your character in game, but it was something that we took for granted, coming from the text MUD world. We came up with a means of mapping color ramps to grayscale pixels on the items, termed “hues,” which allowed us to take every item in the game and not just tint it, but actually change it to have multicolored patterns. This was applied to all the clothing, many of the creatures, all the armor and weapons and hair and skin. (The art team was not happy about this at all – we had to make the case to them that giving the power to the players was critical). UO was the single most varied fantasy world ever created, when it launched.

An excellent example of hue-based “partial tinting” — any parts of the sprite left in true grayscale would map to a palette, and any parts not gray would stay in original colors.

Don’t underestimate what seems like a trivial thing. Dye tubs existed in the world, which spawned with random hues. Dye tubs could be copied. Players could find objects that spawned in the world with rare colors, copy them to a dye tub, and then dye clothes with that rare color, cornering the market on a specific shade of green. There was an economy just for colors in Ultima Online. This led to lily-white wedding dresses, guilds that color-coordinated their uniforms, a pimp named Fly Guy on the docks with a purple feathered hat, and much more. When a bug in the system created “true black” as a hue (a palette with only #000000 black in it) it instantly became a highly coveted color that led to mass murder and economic mayhem. Eventually, I applied colors to metallic ores, and this led to a whole metal quality system as well. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the simple hues system enabled enormous amounts of player dynamics that frankly, still aren’t seen in most MMOs today.

The world was also varied in behavior. The “resource system” has been written about extensively, and didn’t survive to launch. But the underlying data for it remained, and served as the basis for all sorts of simulation. Every patch of water was something you could fish in. You could shear the wool off of sheep, and it grew back. You had to rotate through stands of lumber, as you exhausted the harvestable wood. Name your cow Millie, milk her, then when you chose, slaughter her, and you got meat filets – “filet of Millie.” You could take that to make a steak or a meat pie. “A meat pie of Millie.” For a brief period, you could do that with the meat from another player. Scissors cut cloth. Knives could whittle wood. Looms made cloth, if you had the flax or the wool. Just about everything was craftable — a current list for blacksmiths is pages long.

Lights turned on and off. NPCs moved about, and at first, closed up their shops at night. Bulletin boards in the towns weren’t static dressing, but message centers where players could post notes for one another. Town criers shouted out the latest news, and you could ask any NPC for directions to landmarks. Every NPC was born with a unique name and a rolled-up personality, and they could die and never come back. Fruit trees gave fruit. When you sailed around on a ship, the tillerman told shaggy dog sea stories. The book in the game didn’t just drop random bits of backstory – they did, of course, but you could also make or buy a blank book, and type in your own story, and then that would be added to the possible books that could spawn, and could appear anywhere in the world.

The “Baja Council” all wearing antlers, in uniform

You could create a microphone crystal, and link it to a speaker crystal, and use it to provide loudspeakers for an event. A chain of explosive potions would set of a chain reaction, like a fuse burning down. You could drop things on the ground, and spell out words, or leave a lure of stuff for creatures or animals to pick up. Monsters looted you, if they were victorious. Even when they spoke gibberish, they did so by listening for words you said, and repeated them back to you, which tricked many a player into thinking there was a real language to learn.

The simulation ran deep in UO, so much so that even when the main simulation was turned off, the game still ran as a giant simulated fantasy world. When you look at a typical house screenshot, realize that everything in that house was interactive to some degree, even if it was minor. You pretty much have to come forward in time to Dwarf Fortress or Minecraft to find something comparable in a major game.

This sort of thing unlocked higher order features.

The Golden Brew Players, a theater troupe, meet Lord British

Theater troupes could memorize plays, take over empty stages, and go on tour performing Shakespeare. Costuming was a thing. So were player cities creating their own guards in uniform – players volunteering in shifts to protect homes against playerkillers.

Guilds in UO could go to war with one another, could own a castle, and share a hoard. They could grant titles to the members lower down, and at the start even had a democratic voting system for leadership. Guilds prior to UO were a much simpler affair, and in most online games the list of possible guilds was hardcoded into the game at the outset.

Not that you needed a guild war; UO famously permitted anyone to kill anyone outside of the boundaries of town. The amount of griefing, playerkilling, and bad behavior in UO was legendary, from boring ambushes to boobytrapped chests that blew up in your face to magical gates to tiny islands leaving you stranded in the ocean. This cost us an ungodly number of subscribers, and led to many negative reviews early on.

A player house in UO

Housing in earlier room-based games was quite a different affair, if it existed at all. In UO, the placement of actual structures on the physical map at 1:1 scale with the rest of the world meant real estate value was a real thing, with home values, lack of building space, and much more. This is a thorny enough problem that most worlds back away from it now, because of problems with overbuilding. Eventually, UO allowed full Sims-style ability to design your house within its plot.

An economic analysis of UO by Zach Booth Simpson and a few academic economists

Shopkeepers in UO launched with fluctuating prices and inventory based on local supply and demand. And supplies certainly did fluctuate! Early on there was a failed closed economy, but even with the more typical faucet-drain economy that UO moved to, there was enough there to basically create the market for eBayed virtual goods, as well as constantly changing prices within the game itself. This player-driven economy saw players set themselves up as commercial kingpins, not just as combatants.

Of course, players could just hire an NPC and set it their house, stock it with goods, set prices, and hang a sign out front (yes, you could actually hang a sign… there were about twenty to choose from, and you could select a name for the shop). Players built their small commercial empires this way.

The UORares rune library on the Atlantic server.

And that variety in play was everywhere. Bards whose music calmed angry monsters. Fishermen who pulled up messages in bottles, eventually with treasure maps inside. (When you got to the destination, the game spawned an entire encounter for you; this concept, called a “dynamic point of interest,” allowed the creation of entire orc camps, buildings and all, on the fly, then cleaned up later, leading to a more dynamic encounter map in general). Blacksmiths whose mark on a sword was a big deal, and whose popular smithies would have lines of people outside, because they were the only one that players trusted to repair their sword adequately. Mages could learn spells and inscribe them on scrolls and sell them to others. Museums of “recall runes” existed – teleportation depots, basically, where runes with far flung locations encoded into them sat on display for mages to come to and open mystical gates to other locales.

You learned by doing – and early on, by watching, until we had problems with people inadvertently learning stuff without wanting to – similar to the Elder Scrolls games. This meant practice yards were full of people swinging away at training dummies and practicing archery. Because the power spread between players was actually fairly tight, you didn’t get left behind by others out-leveling you. In fact, a common tactic to take down advanced playerkillers was to go after then in naked mobs because sheer numbers could outweigh the power of even the best-equipped player. Gear wasn’t destiny – everything broke, decayed, wore away. Food spoiled. Stuff could only be repaired so far, and truly rare things were safely put in the safety deposit at the bank rather than risked out in the wild.

Don’t think that this was all an accident. This was consciously designed to be this sort of emergent world, carefully, skill by skill and object by object. There were happy surprises and unpleasant ones, but interdependence, economy, ecosystem, player types and roles – all of this was actively designed for and we attempted our best to anticipate behaviors. Theater troupes? Rune libraries? Real estate pricing? These were surprises that we expected to happen, in a sense. Even the weird ones, like people dropping enough objects in one tile to cause a DDOS attack on players who got close, or people piling up chairs until they could climb onto a player house roof, break in, and loot it dry.

All of this was prodded along by admin intervention: gamemasters who participated in the game, running events, and volunteers who helped them. Large-scale roleplay events and competitions happened all the time, from sporting events (wrestling matches!) to game-wide scavenger hunts. Players dressed up as orcs and actually took over the orc fort, and eventually we just let them run it instead.

Skull the Troll, from the PVPOnline comic strip, was originally a UO monster

This community was actively managed — at first, by me and a few others, then eventually by a team, at a time when the state of the art was .plan files. Short stories and poetry both from the players and from the team were posted on the website – this is part of how Scott Kurtz, today an award winning cartoonist and creator of Table Titans and PVPOnline, got his start. For a while, when we saw that the player-run forum sites were growing too popular and therefore getting too large a bandwidth bill, we quietly hosted them for the players on our own servers. Those sites grew into key parts of IGN and other such major game news sites – we never got a cut.

And every update, we posted up “here’s what we are thinking of changing and why.” There would be an open IRC chat forum, called the House of Commons, where players could join and make their case for different changes, advocate for specific fixes, and in general argue with the developers. Then changes moved through a regular process, from In Concept to In Development and thence to In Testing and deployment, in a transparent open development process that provided visibility on everything we could.

All of this, for a flat monthly free, on the open Internet. And that was a major business shift of its own – even Meridian 59 didn’t launch with that straightforward a model.

If at this point you are comparing all this in your head to World of Warcraft and wondering whether UO had any influence at all, I think that’s fair. Reading player stories from Ultima Online today has this strange quality, where you’d swear that no game could ever have offered that sort of freedom and depth and detail… because no game today does.

Even at the time, competitors ran ads saying “why play to bake bread?” UO was consciously an attempt to create a parallel fantasy universe in which you could live: be it as a craftsperson running a tidy shop, an adventurer deep in the bowels of a dungeon, an itinerant storyteller who made her living picking pockets and roleplaying, or even an explorer who was trying to mark the furthest regions of the map.

Today, if you point at the philosophical heirs of UO, you find them in unexpected places:

Minecraft, which has quite a similar underlying resource system, similarly leveraged for crafting. This is possibly via Wurm Online and Runescape, both games heavily inspired by UO.

Survival games, like PUBG, which recapture that sense of utter fear involved in leaving town. UO was a full PVP world, where anyone could attack anyone outside the confines of town.

Games like Animal Crossing, where that feeling of an ongoing world that lives without you, where you can live a peaceful existence picking fruit and catching fish and decorating a house, remains intact. Even in Facebook games.

A game like Eve Online outright stated an intention to be “UO in space” when it started up.

Were these directly inspired by UO? I don’t know. Housing and crafting and the notion that there are many ways to play the game were definitely things that spread outwards from UO, just as they were taken in their turn from ideas on MUD-Dev and text muds and early graphical games. The eBay market for UO goods created gold farming, and eventually that led to the free-to-play microtransaction model, through a twisty chain of influence.

But it’s impossible to make clear claims. As I mentioned, there were many fellow travelers, on many other projects, and we all swapped ideas and gathered for dinners at GDC. In many senses, UO had almost no “firsts” – you can always find an antecedent for something it did, somewhere, probably for everything I’ve listed above. Convergent evolution means many of the innovations were doubtlessly invented by others as well. At the same time, it’s hard to picture some of these things spreading as they did, in UO’s absence.

I could go on. Just to launch UO, we had to invent early forms of database sharding (the term likely comes from UO), pioneer the large-scale use of VPNs, pioneer character customization, invent seamless multiserver clusters, basically invent modern community management, invent the now-ubiquitous codes on cards for accounts or payment… many were simultaneous inventions, but we basically had to do a whole bunch of new things. You see that pic of the core team up there? The average person in that picture was in their mid or early twenties, on their first game industry job.

No doubt as a consequence of that: many of the things that were tried in UO didn’t work. They broke under unforeseen player stresses – no one had ever designed for thousands of people playing at once in a simulated economy; or they collapsed when the (puny by today’s standards) computers we used as servers couldn’t handle the load. Many were simply bad ideas, as our understanding of player psychology and behaviors evolved. UO chased the industry away from player-vs-player combat for years. To this day, Richard warns people away from trying to tackle a simulated ecology (not me, though, I’m still determined and stubborn). It’s important to realize that UO was a profoundly broken experience in many many ways.

And of course, since players managed to reverse-engineer most of the game in short order, just about everything that worked, or didn’t work, was worked over, redesigned, and recreated by players in the hundreds upon hundreds of “gray shards” created since 1998. At least three server codebases, complete with scripting languages, compatibility with the official client, and, at peak, hundreds of thousands of players, outstripping the official servers. When I got to China for the first time, I learned that UO was well-known there, despite never having launched officially in the country; it was because so many gray shards were run there that it helped create a generation of MMO developers. For a while, UO was probably the world’s most popular user-run virtual world codebase, and thus a true heir to the MUD tradition.

The original painting done by the Hildebrandt Brothers for the Ultima Online box cover

But in the end, if you ask how it pushed the genre forward, I think the answer is that it did so by offering a dream, a dream that even today people compromise on and don’t offer. This idea of a true parallel world with its own life, its own ongoing history, one that doesn’t pander or make concessions for tutorials, bolted-on quests, pay-to-win gear schemes, or any of the other niceties of the business of games… the idea that “what if you just actually modeled another world, in as much detail as possible, and let players loose?”

That’s something that frankly, still isn’t really on offer. So to answer your question: Ultima Online pushed the genre forward by providing an early Camelot, a shining city on a hill that technology wasn’t really yet able to build. It was, and remains, aspirational. It started retreating away from its own lofty goals almost immediately upon launch, and nobody else has managed to make something quite like it.

So that imperfect, barely functional, insane thing: that’s all we got. It’s twenty years in the past – how implausible! And somehow, it still feels like something always twenty more years in the future.

14 Responses to “Ultima Online’s influence”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

I’m curious what influences you’re aware of between UO and ATITD. I can’t recall anything said by Teppy, but that doesn’t mean much since I didn’t have a close eye on ATITD back then.

He was on MUD-Dev too, and came to dinners and the like. ATITD launched in 2003, well after UO had been around a while, so I don’t know how much of the crafting type stuff was inspired by UO, but certainly there are plenty of similarities there.

Good write-up, Raph. I’ll just add: There hasn’t been a game launched with such magnificent depth and breath before or since. Aspirational, yes; but also a HUGE step forward. UO informed all MMO development since 1997.

I didn’t always think that, but it has become obvious over the years.

Your UO retrospectives always bring a tear to my eye :’ D

Great read as always, thanks. Still enjoying UO 19 years (and over half of my life) since I first played. Admittedly I wouldn’t go near the ‘official’ servers these days…

Still loving UO since 1999 when my son gave me the game and invited me to join his guild YEW on Siege. Has been a focus of my retirement for years.. I turn 80 this month… I don’t play much any more but am a member of HOT guild on ATlantic. What drew me to the game was the blue moongates and later was wishing I could gate to the grocery store… grins* and I liked the way folks communicated by just typing.. and sooooo many memories of living and dying and loving and hating… UO will never have an equal.. forever.

Ultima Online’s influence is Great read as always, thanks.

Ultima Online eventually led me back to college to finish my BS in Computer Science and eventually onto my Master of Science in CS with an emphasis in machine learning and AI applied to NIDS. Weird huh? All of that scripting skill gain in a boat in UO translated into thinking about smarter ways to detect unknown network intrusions. It also turned a bitter, anti-social paycheck-to-paycheck tech support knob into a student of gaming, game systems and game AI. And by bitter, I mean Drake from rec.games.computer.ultima.online bitter.

I still have 2 active accounts on production servers to this day.

Thank you!

Raph, while I agree with so much of what you said about the influences of UO, to me the thing that really made it shine was that it allowed players to interact in so many real ways even tho the game itself obviously wasn’t real. I have friends I made in UO who I still talk to to this very day, and more than that, talk to more often than many of the people I know in “real life”.

As you said, there were player shops, and perhaps even better, crafters developed reputations that made people seek out their shops. There were theater troops, bards, tavern keepers, and even, uh, um, rogues. It was this world we all inhabited, and for many of us, it was every bit as important as the real one because of the real people behind our avatars.

So, just wanted to stop by and say thank you to you and the other devs for your creation.

Oh, and, “Thy gold or thy life, knave.”

😀

I remember the first time I heard of UO. I was working night shift tech support at the time and one of the guys there had UO running. I was immediately captivated. It took me back to a world I’d become familiar with playing Ultima IV and here it was not just alive and well but inhabited by thousands of people all playing at once. I was spellbound watching my colleague as he ran around the Trinsic area fighting dragons in a cave as other players ran by on their own adventures. It didn’t take me long to get my own copy of the game and the rest is history. I did eventually tire of the bugs and exploits and the lag so I moved on but I’ll always have a soft spot in my heart for this game(despite the fact that I still largely avoid pvp type games because of my experiences with UO). Such a flawed but equally brilliant game. I’m still amazed when I think back on the scope of UO and all the things you could do. The MMOs that followed provided a more consistent experience perhaps but I don’t think they ever set their sights quite as high as y’all did. There are still people I talk to to this day that I met through this game.

Thanks for all the fun, the friends, and the good memories.

UO is the only game that made me travel to other countries to share a meal, drink and a roof to sleep under – just to meet strangers I was in a guild with.

And I knew I could trust these people because they had shown their trustworthiness in my other home, called Britannia.

So there is that…

Yes, it was a flawed world full of grief and sadness too – but the smiles and love far outweighed the bad. Most of the times. Just like in the real world, I like to think.

“For a while, when we saw that the player-run forum sites were growing too popular and therefore getting too large a bandwidth bill, we quietly hosted them for the players on our own servers. Those sites grew into key parts of IGN and other such major game news sites – we never got a cut.”

That… is amazing and cool and… OF COURSE YOU DID. Because, the biggest part of UO for me, and clearly a few others upthread there, was the community that UO built. I’m still Facebook Friends with some of them 20 years later, and every once in a while, I wonder what happened to the rest of the RCGUO folks. Magnus the Tank Mage in particular. So I think – a big part part of UO’s influence is: Community.

UO was the only game that felt like a world to me. I’ve been waiting for the next generation but I don’t think I’ll ever see it in my lifetime.

Got to do something about the rampant PKing though, if it does ever happen. That could be a purely player driven, social sort of control, but a system is needed.

I’m not even a gamer, really, not before or after UO. It was the world and interactions with it and the players (through that) that caught me up.