Avatar Representation in the Space

A mud is not a mud unless you are in the world the mud represents. In other words, there must be a proxy for you, the user, extant in the simulation. The key factor in considering avatar representation in the space is that the method of representation is completely irrelevant, just as it was with maps. Again, however, there are many ways to accomplish this representation, and they all have differing advantages and disadvantages.

The general term for this proxy in virtual reality circles is avatar. However, muds tend to call them characters, which reflects the gaming heritage of the mud world. The term “character” is derived from the pen-and-paper role-playing games typified by the progenitor of the genre, Dungeons and Dragons. In a role-playing game system (henceforth RPG), a character is essentially your playing piece as well as your proxy in the game: it is a constellation of statistics and data that represent a human (or humanoid, at any rate) walking around in the game setting.

It is fruitful to make a distinction between those elements of this definition that are aspects of game mechanics—let’s call them tangible attributes—and those that are not. An RPG character is defined by a set of numbers on an arbitrary scale. These numbers represent attributes such as strength, dexterity, intelligence, and so on. The attributes listed are generally abstractions, generalizations that represent multiple types of characteristics about a character, but they have direct impact on the operation of specific game rules on that character. For example, the definition of the attribute of Intelligence in the first edition of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons rules reads,

Intelligence is quite similar to what is currently known an intelligence quotient, but it also includes mnemonic ability, reasoning, and learning ability outside of those measured by the written word. Intelligence dictates the number of languages in which the character is able to converse. Moreover, intelligence is the forte of magic-users, for they must be perspicacious in order to correctly understand and memorize spells…1

We can think of this type of character definition as essentially establishing tangible facts about a character—tangible in that they affect the way in which the “laws of physics” of a game, the nature of the virtual reality, operates when interacting with a character.

However, there is a whole other dimension to a character, one that the laws of physics of the world generally ignore. These are intangible to the game’s rules, though they are often not intangible at all in the real world. Examples include physical appearance, temperament, talents, etc. RPGs have not ignored these attributes of a character: even in the first edition of AD&D, there was a “charisma” statistic, and later editions added a “comeliness” statistic as well. As RPGs developed, they began to attempt to simulate more of these aspects of a character using the same statistics systems that they represented other aspects of the game with. Generally speaking these were failures because they didn’t have direct applicability to the game physics. As an example, charisma and comeliness were most useful for very limited applications within the game rules, dealing with the recruitment and management of characters controlled by the “dungeon master” (the guy pulling the strings in the fictional setting—essentially, God to the gamer). As many gaming sessions had no use of this particular moderately obscure subsection of the rules, these statistics were useless and generally ignored. As a result, the player’s ability to communicate and to persuade acquired greater importance than the supposed appearance and eloquence of his character.

So What is Role-playing?

One can think of the elements of a character as acting as a filter on the player. In an ideal situation, the actions that the player can take are limited by the actions that are within the capabilities of the character (as defined by the statistics), and the information received by the player is dictated by the perceptual abilities of the character (again, defined by the statistics). At the same time, one can profitably think of the character as a mask the player wears when participating in the game. Further, one can think of the range of possible characters, and character archetypes, as modes of expression for a player. They are merely different ways to express oneself, in that they offer subtly different media for communicating to others participating in the shared fiction.

To give a concrete example, consider the two following sentences:

This world is boring to me!

I suffer from ennui.

The semantic content of these two is virtually identical, but we perceive them through different linguistic filters, resulting in different impressions of the speaker. The latter is languid, passive, probably educated, and even has a whiff of self-indulgence. The former is angry, desirous of taking action, perhaps a little frustrated.

The effect is increased if we add visual elements to what was written:

This world is boring to me!

I suffer from ennui.

The tonal differences resulting from the typeface are immediate.

A similar effect occurs with characters. They are in many ways the typeface used by the user to communicate and interact with the rest of the virtual world (be it the in-the-head virtual space inhabited by the players of a pen-and-paper RPG, or a mud’s virtual space). The outward appearance of the character (how it is perceived by other participants) is one element here; the filtering of actions and perceptions by the character’s defined statistics is another. To push our typeface analogy even further, the tangible statistics are the typeface, in that it is something that everyone can refer to. The choice of words, however, is still the player’s, and reflects the intangibles.

“Role-playing” is essentially the process of acting in a defined role whilst playing one of these games. “Role acting” is perhaps a better term since the term role-playing has been corrupted by a focus on character advancement, which is to say the game mechanic of upgrading a character’s statistics and abilities over time. In a very fundamental way, good role-playing is getting the words spoken and the typeface in which they are spoken to match up. Just as

I SUFFER FROM ENNUI!

is jarring and bizarre, so is forcing your character to take actions which either his tangible and intangible attributes render implausible or impossible within the setting’s laws of reality. In other words, suffering ennui in that typeface is bad role-playing.

Why does this matter to virtual world design? Because the laws of physics in a virtual world are far more rigid than the ones in a pen and paper RPG. There is no human mediating the effect of these laws and changing reality at a whim. In role-playing circles, the mark of a good game master is considered to be his ability to add and drop laws of physics in service of the narrative events in his world. The actions he takes serve the story and the enjoyment of his fellow players. A game master who obeys the strict laws of physics defined by the rulebook would quickly find his game to be unfun (and therefore without players).

In the virtual world, the game master is the computer, and it has no such agenda. And this makes the nature of characters—henceforth termed avatars—even more critical. Everything the user sees and does is shaped by his avatar—it is his filter on the events that come from the server, and it is his mode of expression within the virtual world. And whereas in a pen and paper gaming session the other players are aware of the true characteristics of a player because the player typically expresses himself as himself, merely choosing to conform to things that the character might do; in a virtual setting, the other participants only perceive the mask. The actions they see are only what the character does. For them, the other player is the avatar.

Identity

This brings about the issue of identity. A player’s online identity is largely a result of the intangibles, not the tangibles. If the player is not a careful role-player, what will happen is that the intangibles that leak through (such as eloquence, prejudices, moods, analytical ability, leadership, etc) will be completely unrelated to and unaffected by the formal definition of his identity within the virtual space, which is concerned only with the tangible elements such as statistics. Thus we get the phenomenon of the character with supposedly low intelligence that is the leader of his peer group.

The way to think of it is that the mud server relates to a user based on the tangible statistics, because they are database entries. And other players relate to the user on the basis of the intangible attributes. But these intangible attributes are not exactly the intangible attributes of the actual human behind the mask—rather, they are filtered intangibles that are modified both consciously and unconsciously by the user based on the inputs he receives from the server and based on the nature of his online identity.

This is a heavy burden for an avatar to carry. Fortunately, avatars are iconic and not representational. And this means that they can carry a much heavier semantic burden. In Scott McCloud’s seminal book Understanding Comics,2 he defines cartooning as “amplification through simplification.” What he is getting at is selectively picking elements of a picture to concentrate on and make more important—like, perhaps, the way in which we select intelligence, strength, dexterity, and other such attributes to serve as an abstraction of a person in an RPG. He also says,

This is a heavy burden for an avatar to carry. Fortunately, avatars are iconic and not representational. And this means that they can carry a much heavier semantic burden. In Scott McCloud’s seminal book Understanding Comics,2 he defines cartooning as “amplification through simplification.” What he is getting at is selectively picking elements of a picture to concentrate on and make more important—like, perhaps, the way in which we select intelligence, strength, dexterity, and other such attributes to serve as an abstraction of a person in an RPG. He also says,

When two people interact, they usually look directly at one another, seeing their partner’s features in vivid detail. Each one also sustains a constant awareness of his or her own face, but this mind-picture is not nearly so vivid; a sketchy arrangement… a sense of shape… a sense of general placement. Something as simple and basic as a cartoon.

He goes on to note that the only thing more abstracted is text itself.

The implications for the avatar are clear. In the virtual world, what we are seeing is the cartoon selves of different individuals interacting directly. McCloud says, “Icons demand our participation in order to make them work. There is no life here except that which you give to it.” The process of fleshing out the reality of an icon, McCloud terms “closure.” Media which depend on this sort of thing were termed “cool” media by Marshall McLuhan—comics is one such, and television is another. A virtual space, because of its interactivity, of course cannot fall into the same category, but it is interesting to see that one aspect of virtual worlds, at least, can be regarded that way.

In order to identify with an avatar in virtual space, we must make a very large leap of “closure.” However, the amount of closure required has been reduced over time as the tangible qualities of avatars expanded. This is complicated by the fact that the filtering performed by avatars is still very imperfect: just as in the paper RPGs, the player’s personal abilities to communicate and lead are more important than the alleged abilities of the avatar that represents him.

An interesting possible extrapolation of McCloud’s commentary is that it may very well be the fact that the typical virtual world avatar is an abstraction that makes them so easy to identify with. They serve as a direct projection of our unconscious selves in that like that self, they are a “cartoon” in McCloud’s terminology. This makes them extremely easy to identify with. This argues in favor of reducing the realism of our avatar portrayals as we design these environments, if we wish to have tighter identification. Interestingly, social spaces are those with the least definition to their avatars. They have a much higher proportion of intangible avatar characteristics, and correspondingly less world physics to relate to. At the simplest end of this scale lies The Palace, the project with which Randy Farmer and Chip Morningstar of Electric Communities followed up Habitat. This mud uses a simple room-based model, with only a backdrop screenshot and little sense of spatiality to convey the “location.” And avatars themselves range from full cartoon bodies to essentially disembodied cartoon heads, floating against this backdrop, speaking in comic-book bubbles.

In a similar vein we see The Realm, originally developed by Sierra. Its side view, shared by BSX muds, Habitat, and The Palace, deliberately invokes a comic book in its imagery and artistic style. The player in the figures on this page went on to play Ultima Online, where the greater realism of the artwork no doubt prevented her from finding as good a representation of herself.

In a similar vein we see The Realm, originally developed by Sierra. Its side view, shared by BSX muds, Habitat, and The Palace, deliberately invokes a comic book in its imagery and artistic style. The player in the figures on this page went on to play Ultima Online, where the greater realism of the artwork no doubt prevented her from finding as good a representation of herself.

Of course, even this representation of Janey isn’t really the way she is generally perceived in the game: Ultima Online offered a higher-detail version of the character and the regular version, which is what most people could see. And this version looks much more like a cartoon again, as most of the detail is lost, including (most crucially) facial features.

Of course, even this representation of Janey isn’t really the way she is generally perceived in the game: Ultima Online offered a higher-detail version of the character and the regular version, which is what most people could see. And this version looks much more like a cartoon again, as most of the detail is lost, including (most crucially) facial features.

In a more realistic environment, like Asheron’s Call, not only do facial features follow “heritage groups” (meaning, you can get Asiatic features, or Caucasian, and so on) but you can pick from an assortment of eyes, noses, mouths, and so on. This allows you to more carefully craft something that mirrors your mental image of your avatar, but also may result in removing some of that iconic quality in characters.

The flip side of the coin in all of this, of course, is whether the iconic nature of the other avatars in the space makes them easier to objectify, or easier to empathize with. In general, the more cartoony spaces tend to have less problems with antisocial behavior, but that may result from self-selection of the participants, rather than any effect of the artwork. This remains as a potentially fruitful area of research.

It is a major mistake to minimize the importance of identity in your virtual space. It is also a mistake to assume that it can serve to tie a given player to your space (say, perhaps, for the purposes of charging an ongoing fee). Your environment offers an opportunity to incarnate in bits and bytes a persona that the player normally has only in their mind. But it is almost certain to be an incomplete mapping. The primary persona is and will always be the one visualized in the player’s head. As a result, it is eminently portable from world to world. There are countless incidents of role-players carrying a given character, complete with name, behavior, and even similar tangible attributes, from game to game, over the course of as many as twenty years.3 The characters will not ever map perfectly, but they map as well as they ever do, since any mapping whatsoever fails to match the vividness of the conception in the player’s head.

That said, it is a wise thing to offer as wide a range as you can of means to reinforce an avatar’s identity, because it increases the chances of a player finding a mapping for the persona they wish to present. In addition, playing dress-up with a miniature doll is just plain fun, for either gender (though men may choose not to admit it), and the more choices you offer for avatar identity, the more you can offer that fun. It is no accident that Ultima Online and other games have termed the avatar customization window the “paperdoll.”

Names

In its most primitive form, an avatar is just a handle, or “nick” to use IRC terminology. In other words, just a name. The name is in fact one of the first elements to be removed from avatars when designers of muds start getting more creative. Many muds, when they evolve out of standard codebases, start replacing the standard descriptions of people:

John is here.

with more descriptive tags based on physical characteristics:

A tall dark man with horrible scars is here.

This then requires the observing player to either recognize the description and tie it to a name, or to examine the player more closely in order to ascertain the name. Some proposed designs go even further, allowing all names perceived by a player to be completely relative and arbitrary. Under such a system, we have no global namespace—a given name is in the perceiver’s eyes. Global namespace is a term ripped from programming, of course. However, it has interesting and special characteristics for mud design. Whereas one player might see:

John has arrived from the west.

another might have encountered John before and stored a custom tag for him, resulting in output like:

The jerk who tried to hit on me has arrived from the west.

This has interesting possibilities for the future, when it is likely that the large scale of online communities will demand “tickler files” of similar design, even if the global namespace remains intact.

Unique names are another issue related to the global namespace. Most muds actually store individual player’s data files indexed off the name. Thus, the requirement for unique names arises from a basic architectural decision in the server. They serve as invaluable tracking tools for the mud admin and also for other players—in fact, arguably they are more important to the other players than to the admin, because admins generally have other methods of identifying a particular player. Much of the communications infrastructure of a typical mud relies on unique names; when you need to send a message to a player remotely, the means for doing so is to send it to the unique tag you have for them: their name.

Constancy in names is vital to players for more than interface reasons. Without it, there can be no semblance whatsoever of social transmission of information regarding the behavior of fellow avatars. Without this reputation-based curb on behavior, avatars are likely to run amok.4 The stigma of violating social codes falls away if true anonymity is available. Hence many thinkers in the field refer to the threshold as being pseudonymity.5 This is similar to a handle on CB radio: nobody may know your real name, but you are sufficiently tied to the handle you use that it can establish a reputation of its own, and you can come to value it as much as you value your name in the real world. And indeed, one can see the instances of pseudonymity having taken root in players’ minds when they make statements like, “I’d like to try out that new game, but if I can’t have my name in it, then I’m not going to play.”

Clearly, conflicting desires here lead to both the need for unique names and also the imperative of letting players choose the pseudonym that suits them. The only major mud to ever launch without unique names was Ultima Online. As a result, it also lacked effective in-game communication tools, and problems with impersonation of other players ran rampant. At the same time, large-scale muds (and in fact, any large scale system with unique names, such as America Online) run out of plausible names extremely quickly—this was the reason why UO made the choice it did. Inability to obtain a particular handle upon first login is often cited by players as a reason for not staying on a mud. There are well under 5,000 names in common usage in the English language, and even the addition of fantasy names does not account for enough handles to cover a player base of over 100,000. EverQuest handled this by creating a random name generator that simply used syllable combination to generate gibberish; the results were far from satisfying and failed to meet the best test of a name: strong mnemonic identification. Another frequently suggested solution to the problem is to allow duplicate names but expose some sort of unique identifying number or code for every player to the populace at large. This also fails the mnemonic test, of course, but doesn’t preclude multiple “John Smiths.” A better solution would involve breaking down a name into components, such as first name, surname, place of origin, and other such identifying characteristics. Thus there could be countless Johns, and even many John Smiths, but only one John Smith of Avalon.

Descriptions and Appearances

The other standard piece of information making up an avatar’s identity is their description or appearance. Depending on the system used for displaying the environment, the physical description of the avatar may be textual or graphical. In addition, depending on the system, the avatar may also have optional material (always textual) that can be entered in to describe their character in greater detail. Players often make use of this to embellish upon the bare strokes that the standard description allows.

The most interesting aspects of descriptions and this type of profile are the ways players reveal themselves through them. The very first step is that of choosing a gender.

Currently, the player base of commercial graphical muds is over 70% male. However, the gender breakdown of avatars within the game shows a far higher percentage of female avatars. Similarly, the population of text muds in general shows that the majority of those who play are in fact male, but that the amount of female-presenting characters can approach 50%, depending on the nature of the game played.

In general, female players tend to be attracted to the more social spaces, whereas the goal-oriented systems tend to be predominantly male. However, in both spaces, numerous males choose to play female-presenting avatars—enough of them, in fact, that it’s a standard joke in mudding circles that odds are good that your netsex partner was a fourteen year old boy, regardless of what gender you are and regardless of what genders you presented to one another via your avatars.

There are basically three reasons given for this behavior. One is a particularly pragmatic reason: female-presenting players tend to get special treatment in muds, perhaps because the vast majority of the players behind the masks are actually males. The female characters tend to get assistance more quickly than males in dealing with the tribulations of being a newbie, and they tend to be given gifts of equipment and items. While they tend to get sexually harassed and propositioned at an alarming rate, by and large, they have a smoother online experience than those who are male-presenting. To this end, many of the most blatantly female characters are often playing up the supposedly feminine behavior with the explicit intent of getting favors and stuff.6 Conversely, many females choose to present as males in order to avoid the sexual harassment.

The second reason often advanced is simply “to see what it’s like on the other side.” It’s hard to quarrel with this, nor is it worth the time to investigate the psychology behind this motive. Players who give this reason often report a sense of liberation with playing the opposite sex, of freedom from traditional expectations and gender roles. Others report greater insight into the opposite gender as a result of having experienced life “in the other person’s shoes.” The gender identification with one’s character can become so complete that male players report having become angered at being forced to wear overly revealing clothing on their avatars (feeling the sting of sexual objectification), and female players report having fallen into stereotypical demonstrations of machismo, acting protective of female-presenting avatars even when knowing their gender to be male, etc.

The third reason is the most banal of all: to entice someone into tinysex,7 only to publicly post logs of the deed in order to embarrass them.

The curious thing about gender in cyberspace is that it is both inescapable, and oddly fluid. It is generally easy to tell who is the male playing at being female when they start out, because they are often too crude or too direct and too sexual when dealing with other players. But an experienced cross-gender role-player can and will fool players of both genders without great difficulty, precisely by acting more like the gender that they are presenting than like a panting teen in the throes of hormonal flux. The result is that while avatars are generally strongly gendered, and presented sexuality is extremely important for social interaction, it may not correspond to the gender of the actual player.

An interesting outcrop of this is the way in which female and male players choose to present their avatars. Regardless of whether they are playing across genders, the choices follow patterns. The female avatars are largely beautiful, or mysterious, or impish, or plucky, or in general appealing. You very rarely see, regardless of the gender of the player, an overweight, or dull, or unappealing female. Similarly, the male characters tend to either be noble, or roguish, or mysteriously scarred, etc. The presentations are uniformly, regardless of player gender, sexually attractive. However, within this very narrow range of actual human appearance, there is still tremendous variety presented. Certainly the appeal of presenting a beautiful female avatar to the world is likely different for the male and the female player, but nonetheless, avatars designed by each tend to be similar in that way.

A phenomenon often observed in the real world is that what we commonly term “civility” is often related to the number of members of the opposite sex present in a discussion. Interestingly, mud civility seems to be directly related to the number of female-presenting characters present in what has largely been a boy’s club. This leads to the interesting conclusion that perhaps forcing an equal balance of the sexes in your online space may well lead to a more easily administrated environment.

On many systems, a somewhat less popular third alternative to the standard genders exists: the gender-neutral character. Anecdotally, most neuter characters are played by females, presumably for reasons similar to why they would choose to play a male character; however, supposedly male characters play them far less frequently. No major commercial systems thus far have allowed gender-neutral presentation within the context of a generally gender-aware system; however, several chat spaces, such as the original incarnation of The Palace and the 3d environment WorldsChat, have offered systems wherein the avatars were much more iconic, often being symbols, smiley faces, or anthropomorphic representations of animals.

Of course, anthropomorphic representations of animals have given rise to an entire subtype of social space, commonly called “furry.” The original FurryMUCK is infamous for both its animal-based avatars and for its general acceptance of sexual activity between avatars—so much so that saying you visit a Furry game is often considered to mean that you like anonymous netsex. The sole graphical Furry world is Dr. Cat’s Furcadia, which is perhaps the most successful design for a socially oriented space thus far. In a Furry environment, players choose from a variety of animals to incarnate, with the various animals often suggesting something about the character or nature of the player behind the avatar. These critters are generally strongly gendered, rather than the animal nature of the avatar taking prominence in the depiction. Again, it is avatar as filter of experience and as mode of expression.

Of course, anthropomorphic representations of animals have given rise to an entire subtype of social space, commonly called “furry.” The original FurryMUCK is infamous for both its animal-based avatars and for its general acceptance of sexual activity between avatars—so much so that saying you visit a Furry game is often considered to mean that you like anonymous netsex. The sole graphical Furry world is Dr. Cat’s Furcadia, which is perhaps the most successful design for a socially oriented space thus far. In a Furry environment, players choose from a variety of animals to incarnate, with the various animals often suggesting something about the character or nature of the player behind the avatar. These critters are generally strongly gendered, rather than the animal nature of the avatar taking prominence in the depiction. Again, it is avatar as filter of experience and as mode of expression.

A similar artifact found in nearly all goal-oriented muds is the practice of having avatar “races,” which are templates based on humanoid fantastical races such as elves, dwarves, or various alien creatures. Selecting one of these generally has an impact on your tangible statistics, but also enriches the profile by carrying with is expected behavioral patterns and certain restrictions in appearance. Races tend to be extremely popular. A statistical survey at one website8 showed not only the usual suspects in the top ten, but an astounding range of over 70 different races available in a range of different muds.

In examining descriptions (and in designing the systems that allow players to create them) the primary thing to consider is how they allow the players to express themselves. A player’s avatar is largely about wish-fulfillment in one way or another, and the range of wishes they can fulfill is directly limited by the author of the space. Much psychological hash can be made from the choices a player makes in their descriptions, but we should not forget that people are limited to the choices that the designer offers.

When interacting from behind the mask of a description, the things a player says are inevitably shaped by the mask they wear. Given that the mask itself is an expression of the player, what others perceive is not so much different from the personality of the player as it is a refinement and exaggeration—hearkening back to McCloud again, a cartoon. The natural disinhibition that occurs leads to unvarnished truths being spoken and actions taken that would not otherwise have occurred to the player. But these actions and words are still ineluctably part of the player’s expression. Players wearing a mask reveal more of themselves, not less. As Shakespeare put it, these avatars, our actors, are all spirits—and like all spirits, they in some way represent an essence, and therefore an essential part, of what we term our “selves.”

Profile

Identity, of course, does not spring into being overnight. It accretes over time, layering onto the original core notions of self, and is particularly shaped by what others think of the person in question. So it is in virtual worlds as well: a given avatar’s character evolves significantly over time, both because of adapting to the possibilities the space presents, and because an avatar, like a person in the real world, is very much shaped by other’s perceptions.

In cyberspace, this manifests as something termed the profile. Essentially, this is a historical record of some sort that documents what the avatar has done—perhaps even including elements from before the avatar began to actually exist, fictionally added into the record to provide more of a context for their actions. For example, a player of a World of Darkness MUSH likely ascribes a fairly detailed background to their character, and makes this extended history publicly viewable by anyone interacting with them so that others may know in what ways to address them or respond to their presence in a manner that fits with the total fictional immersion that is the goal of this sort of role-playing-enforced space. In contrast, many systems may have nothing at all for this, or may simply allow the player to insert this sort of background material in their description.

In cyberspace, this manifests as something termed the profile. Essentially, this is a historical record of some sort that documents what the avatar has done—perhaps even including elements from before the avatar began to actually exist, fictionally added into the record to provide more of a context for their actions. For example, a player of a World of Darkness MUSH likely ascribes a fairly detailed background to their character, and makes this extended history publicly viewable by anyone interacting with them so that others may know in what ways to address them or respond to their presence in a manner that fits with the total fictional immersion that is the goal of this sort of role-playing-enforced space. In contrast, many systems may have nothing at all for this, or may simply allow the player to insert this sort of background material in their description.

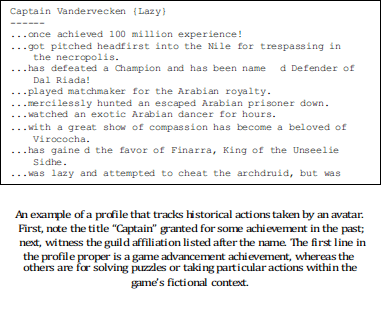

Beyond the player-entered history, there is also the tangible history of the avatar. Depending on the system, this may be as much as a detailed list of deeds done and significant accomplishments presented publicly, or as little as the level they have achieved on some arbitrary game advancement ladder. It may even be as little as a record of infractions kept by the administrators for the purpose of determining when a given user needs to be ejected from the service.

An evolving user profile of this type is not only critical for being able to maintain the service, but if publicly visible, serves as a powerful community builder. Awards for good behavior, virtual pillorying of virtual criminals, notable quests completed, and so on, all serve to reinforce the notion of accountability for one’s actions, which in turn helps reduce the level of sociopathic behavior online. Making the profile visible to others helps innocents quickly identify troublemakers, and helps new arrivals quickly find role models.

And in many environments, the ability to interact with objects, carry them, and wear them in a publicly visible fashion, has resulted in the term equipment being applied to those aspects of an avatar’s profile which are acquired assets one can remove at any time. Equipment is traditionally just a list of wear slots (locations where items are worn) and the corresponding objects; even in graphical systems, this convention is followed, but the display is usually done by superimposing the images of the worn items onto the avatar’s body on a paperdoll, thus extending the appearance. In that way, profile and description serve to reinforce one another in the creation of identity.

And in many environments, the ability to interact with objects, carry them, and wear them in a publicly visible fashion, has resulted in the term equipment being applied to those aspects of an avatar’s profile which are acquired assets one can remove at any time. Equipment is traditionally just a list of wear slots (locations where items are worn) and the corresponding objects; even in graphical systems, this convention is followed, but the display is usually done by superimposing the images of the worn items onto the avatar’s body on a paperdoll, thus extending the appearance. In that way, profile and description serve to reinforce one another in the creation of identity.

In almost every system out there, a user’s profile includes tangible statistics that drive the capabilities of the avatar. The commonest use of this is to turn on a flag or reach a threshold on an advancement ladder that confers special powers within the environment—this essentially allows access to modify the laws of physics of the game under which all avatars normally labor. There are various terms for this type of avatar, most of them arising from the role-playing game origins of muds: god, wizard, immortal, etc. Usually, this aspect of an avatar’s profile is publicly visible unless the avatar is choosing to appear incognito.

Other uses for these tangible statistics that grant commands or capabilities are to provide increased reward to players over time as they climb an advancement ladder. Typical is the granting of new spells, skills, or access to new pieces of equipment or items that they can make use of. It’s very common to see “level” as a displayed element of an avatar’s profile. There are also tangible statistics that serve to drive the avatar’s interaction with the game rules, such as attributes for intelligence or strength. These also, typically evolve over time.

Perhaps the most interesting type of evolving profile is the generic class of profiling tools called reputation systems. These are systems whereby fellow users of the space are granted the ability to add to the profile of any given user with whom they have an interaction. Typically, when some transaction or interaction occurs, each user has the ability to rate the behavior of the other party. The cumulative totals of positive and negative interactions thus result in easy-to-read ratings that anyone can use. Various auctioning systems on the Internet such as eBay make extensive use of this practice, and Ultima Online attempted to use it to curb antisocial behavior.9 The reason why this addition to the profile is important is because of the inconstancy of communication in virtual spaces—it’s far too hard to spread word of a malcontent or evildoer, but reputation systems essentially leverage the avatar’s profile to do it for you.

Profiles often modify names, usually with the granting of titles. Group affiliations should be a major part of an avatar’s profile, and the more facilities provided by the virtual world to allow display of these affiliations, the better. There have been many examples of users choosing to start an avatar over from scratch, throwing away all advancement, just in order to insert their guild affiliation or a family name in their avatar’s name because the game system did not support a separate field for it.

Page 10 of the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Players Handbook, by E. Gary Gygax, published by TSR in 1978. ↩

HarperPerennial, 1994. ↩

A poll by the RPG news site The VaultNetwork (http://rpgvault.ign.com) found that 57% of players had played the same character or persona in multiple games, campaigns, or settings. ↩

One logical extrapolation of this is the conclusion that new arrivals in your world, who do not yet have any attachment to their name and thus to their online identity, have no social curbs on their behavior. In the real world, we term these people sociopathic. All of your new arrivals in a virtual world are “virtually” sociopathic, until they acquire sufficient empathy for their own identity and for other players. ↩

Among them, Dr. Amy Jo Kim and Julian Dibbell. ↩

This has been demonstrated in research many times over by now—gender presentation and the phenomenon of cross-gender role-playing has resulted in more papers and theses than any other topic on muds. I can offer empirical demonstration as well: as a female-presenting character in the company of several male-presenting characters, I found myself offered an administrative position by the (male) head administrator of a mud, whilst the others in my company were threatened with character deletion. All three of us had been guilty of the same offense, but the treatment of my character was manifestly different. Later I learned that this same admin had a habit of propositioning female-presenting characters, giving them gifts in the real world, etc. ↩

The term “tinysex” derives from the TinyMUD codebase. Numerous sorts of activities undertaken in both the real world and virtual world have had the word “tiny” attached to them in order to make clear in which realm (virtual or real) the activity occurred. ↩

The now defunct Game Commandos site at http://www.gamecommandos.com. ↩

Since in UO you could only add negative ratings, and then only upon a fairly significant negative action being performed against you (e.g., when someone killed you), the reputation system did not really function as a useful indicator of a character’s past. Later on, the ability to grant positive points on a different scale was given, but since that scale had too many automatic events that granted points, it didn’t accurately reflect the opinion of other players. ↩